We perceive our world more and more through digital senses. It’s there in the way we map it, scan it, and digitize it into video games. It’s no surprise then that therapists are exploring new technologies for tools and exercises to help people cope with their fears and anxieties. This week we’re exploring three fascinating techniques that are just the beginning.

Treating Phobias With Augmented Reality

If you are afraid of spiders, the Phobia Free app will place one into your home under your control and in a condition that will make it easy for you to overcome your anxiety. You can place it into your bathtub, for example, and then watch it through the camera in your iPhone or iPad. When you need it to go away, a tap of a button will make it disappear. That’s the trick of Augmented Reality, a technology that mixes computer imagery with the view in your camera. The spider isn’t real, but it moves as if it is, even reacting and climbing over your belongings.

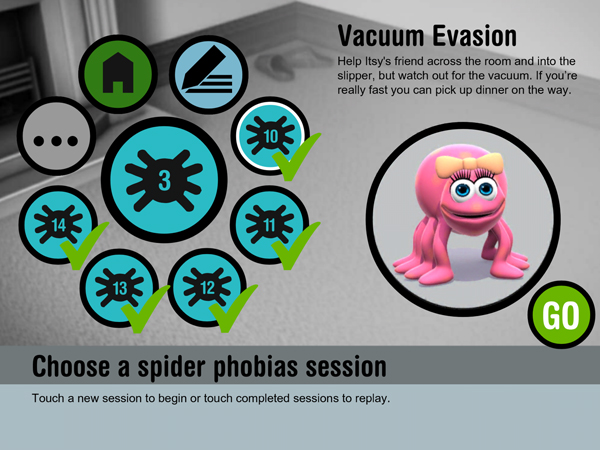

Of course the app doesn’t trigger that experience until long after you’ve completed a series of exercises that explore coping strategies, relaxation techniques, and a chance to record and evaluate your anxieties over time. It begins with a cartoon spider named Itsy who is unrealistically pink, has big feminine eyes, and is very, very shy. Through a series of game-like exercises, you help her overcome her fears and protect her from things like vacuum cleaners and brooms.

As you progress, the body of the spider gradually changes. Its legs become more spindly, it’s eyes small and beady, and its colouring gradually darkens. The idea isn’t just to get you slowly used to a spider’s frightening appearance, but to associate the shy, vulnerable personality of the cartoon with a real spider in your home.

(Fun Fact: House spiders prefer to stay in their cobwebs out of sight. Chances are if you see one out and about, it’s a male looking for a girlfriend. Something to considering when you decide between having to kill or rehome the lonely fellow)

It’s a well-made app with fluid animations, careful exercises that are easy to follow, and a genuine sense of engagement. The National Health Service in England has endorsed Phobia Free, adding it to their own recommended Health App Library.

Dr. Russell Green and his team of healthcare professionals say they developed the app as a tool for patients to take home so they can work on their condition when they need to, wherever they are. They plan on creating more apps to deal with other animal-based phobias in the near future.

Treating Addiction With Virtual Worlds

For good or bad, games like Grand Theft Auto do an amazing job of recreating real-world bars, casinos, parties, and crack houses. It’s not just that they capture the look and feel of such locations, but it’s the way they populate them with convincing characters and unexpected details. Dr. Zack Rosenthal at Duke University has been using custom versions of these game scenarios to help recovering addicts cope in with their cravings.

A patient participating in Rosenthal’s program will be asked to enter a video game version of their local neighbourhood, where the team has captured familiar streets to walk down and in some cases the very bar the patient used to habitually visit. They get the details down pat, even to the point of leaving their patient’s favourite seat empty and waiting.

The more convincing the simulation, the thinking goes, the easier it will be to trigger physical cravings in a therapist’s office. When that happens the game can be paused and the therapist can help their patient cope in the moment.

“Once the cravings go down, there’s sort of this magic moment where learning has occurred,” says Rosenthal. “We think the brain is learning that, even if they are exposed to substance-related clues, they don’t actually have to use.”

The hope is that by referring to the real world in a video game, it will make it easier for a patient to carry their lessons with them to the outside.

As with most exposure therapies, the idea is to present scenarios that can become challenging gradually. A virtual bar can start off underpopulated and low-key, where the only conversations are ones you overhear, and then with future sessions grow into a vibrant place where people come up to engage you directly. Therapists can even add a specific brand of beer, offer chips to a favourite game, or leave a key piece of drug paraphernalia lying out in the open.

It’s becoming better understood that the triggers for substance abuse are as much about context of use as the substance itself, that therapists need to also recreate social settings and lifestyle habits in their lessons, that where you sneak off to have a smoke or who you like to drink with is as much a trigger as the bottle or packaging things are sold in. These are things that video games can recreate very well.

When Rosenthal began his program more than seven years ago, his team was using video game consoles to run their simulations. The Occulus Rift, a new video game system being hailed as the comeback for virtual reality, is expected to launch later this year. It’s a headset that accurately matches the movements of your head to that of a video game world around you. It’s being hailed as the next big thing in games and movies, but for research teams like the one at Duke University, it’ll mean a leap in exposure therapy as well.

Treating Schizophrenia With Avatars

Imagine if the thoughts you tactfully keep to yourself were to take on a life of their own and be spoken aloud by someone else, someone very real to you, but invisible to others. That’s the long-standing theory about how Schizophrenia works. A recent discovery suggests that one way to silence such voices is to talk back to them, that by engaging them in a discussion it’s possible to resolve the underlying issues and make them reduce their critical nature if not disappear completely.

“The problem with dealing with an invisible voice is that you get none of the cues that normally sustain dialogue,” explains Dr. Julian Leff, a research psychiatrist at the Institute of Psychiatry in London “because we rely heavily on people smiling, nodding their head, maintaining eye contact, and of course all of that’s missing with an invisible voice.”

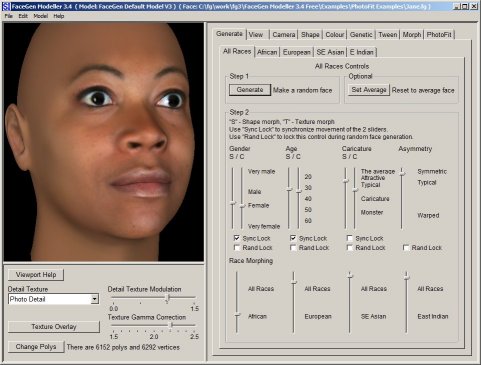

Dr. Leff has been encouraging his research patients to create computer avatars to match the voices they hear. They use the same kind of software video game players use to make their characters in role-playing games where, in addition to choosing hair and eye colour, skin complexion, and face shape, they can also choose how high the cheekbones are or sculpt the chin to an specific point.

Because the features of the resulting Avatar match the way the patient perceives the voice in their mind, it can be used to confront the voice and control the resulting dialogue. The therapist can take on the role of the voice by wearing a headset and connecting to the Avatar from another room. With voice-changing software, the therapist performs as the Avatar and guides their patient through the confrontation.

Many patients with this condition have voices that are hostile or abusive. Using the Avatar, patient and therapist can simulating these hostile encounters and then, over the course of six sessions, work together to guide the dialogue towards a friendlier and supportive state. An MP3 recording of these sessions are given to patients so they can replay them as needed at home.

“In my view, because the voice is no longer threatening,” explains Leff,” the patient is able to re-integrate that externalized voice into their mental space. They can use the MP3s to listen to the sessions whenever they hear the voice, and this may explain the further improvements after the aid of therapy.”

It’s not an approach that will work for all patients living with schizophrenia. Those with multiple voices will have to wait for a system that supports multiple Avatars while some patients opted out of the therapy because their voices warned them against it.

Those who finished their Avatar Therapy said they were hearing from their voices less and less, that they were expressing fewer critical thoughts, and patients began to show dramatic improvements in their self-esteem. Since one in ten patients who hear abusive voices tend to commit suicide, this is important progress.

Based on those positive results, Leff’s department has partnered with other researchers on a new three year study to better explore the potential of Avatar Therapy. Another study from the National Health Institute, published last week in the Lancet, shows Speaking Therapies, which follow the same concept, helping to reduce the need for anti-psychotic medication and can be a viable compliment to traditional long-term treatment.

The therapies made be virtual, but the positive results they provide are turning out to be very much real.